In the natural world there is one element so omnipresent, so pervasive, so vital that it has become a blind spot — like air, like water, it is something we take for granted. It is grass.

Grass supports more fauna than any other type of plant; it supports more human beings than any other food source.

It is pervasive, covering a quarter of all land on earth; it exists even in areas too arid to sustain trees. It is indestructible, and has survived fires, floods and the deepest of freezes. It is the connective tissue that ties disparate life forms together.

We don’t think of it that way, but 70 per cent of our daily diet derives from grass. Rice, maize, wheat, barley and other such species are grass forms that have sustained us since the advent of agriculture; species we have selectively bred over a span of time that dates back to before recorded history.

India has an astonishingly diverse selection of grasslands. There is the Terai, the tall grass that grows along the floodplains of the Ganga and the Brahmaputra. The Terai is dominated by elephant grass, spreads along the foothills of the Himalayas, and hosts both the largest concentration of mammals in the country and, by virtue of being the most productive agricultural belt in India, supports the highest human density.

The grasslands of Central India, sandwiched between swathes of forest, is one of the last strongholds of the tiger. The area is astonishingly fecund, supporting many different species of herbivores which, in turn, sustain endemic predators such as the tiger.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/KalyanVarma__D1093662-1000x666.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/KalyanVarma__D1093662-1600x1065.jpg,(large)])

The Shola-grassland ecosystem in the higher elevations of the Western Ghats is another unique natural grassland. While the Shola or the montane evergreen forest here are highly biologically diverse, the grasslands surrounds these also support specialised and endemic species such as the Nilgiri Tahr and Nilgiri Pipit.

The most threatened and endangered, however, is the dry grassland, the tropical savanna found in the arid parts of the country where annual rainfall is too sparse to support forests. It is also the most officially neglected — less than two per cent of this area falls in the protected category.

Collectively, these grasslands host some of the rarest wildlife species in India — the Bengal Florican, One-horned Rhinoceros, Pygmy Hog, Wild Buffalo, Hog Deer, the Swamp Deer in the Terai, the snow leopard in the high-altitude steppes, the Great Indian Bustard in the dry, short grasslands, the Lesser Florican in the monsoonal grasslands of western India, and the Nilgiri Tahr in the Shola grasslands of the Western Ghats.

And then there are the people: a majority of those in rural India depend on these grasslands, which are basically village commons, owned by the revenue department but set aside for the community’s use. The primary use is grazing — India has over 500 million livestock, thus making the village commons the backbone of rural India. And much of these commons support as much diversity as protected grasslands — studies have for instance found that sustainable populations of species such as the Blackbuck and the Wolf are also found in the commons outside of the protected grasslands.

Wastelands

Given the criticality of grasslands, you would imagine that the government would be laser-focussed on protection and conservation. If the reverse is true, it all boils down to nomenclature: where we see grass rich with possibility, the government sees ‘waste’ — the official classification is not ‘grassland’, but ‘wasteland’.

In this case, there is lots in a name. India’s total land area is around 329 million hectares. Of this, the government classifies 90 million hectares as “wasteland” — that is, non-productive land; a definition that militates against the fact that about 40 per cent of our 1.3 billion population depends on this land for livelihood.

The use of “wasteland” dates back to the 1600s, when British political philosopher John Locke coined it as a catch-all word to denote any land that is not privately owned. Locke argued that the returns from privately-held lands far exceed that from commons, and used that argument to promote the reduction of “wastelands” through privatisation.

Arguing the case with reference to British settlements in Africa and in America, Locke said :

“…by bringing more lands into intensive cultivation, English colonisation of the Americas would raise agricultural productivity and individual wealth worldwide and provide a source of increased trade from which England’s population as a whole would benefit. …”

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/KalyanVarma__4124330-1000x666.jpg,(large)])

This theory formed the bedrock of the British view of land-use in India and other colonies. With Independence, India shed the colonial yoke but not its underlying philosophy; the first elected government of Independent India continued down the path of intensive agriculture to make “wasteland” productive.

According to J.W. Nicholson (1926)

“ Nature requires protection from men, as it is a common failing in human nature that whenever any product is found in abundance its use is abused without thought for the future. Left to themselves, the villagers take no care of their forest.”

(Source: Chapter II, The need for a Forest Department, in the book “The forests within Bihar and Orissa”)

Based on this economic philosophy, the young Indian republic under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru and subsequently Indira Gandhi saw all commons that were being used by pastoralists as un-taxable, hence “wasteland”. Building cash reserves for the country was critical at that point and all the lands were unilaterally taken over by the state and then divided among agriculturists on the assumption that private ownership would intensify cultivation and thus produce more taxable income

The natural outcome of this philosophy was the formation of the National Wastelands Development Board, under the Ministry of Environment and Forests. It’s purpose was to treat all commons as wasteland and develop it for agriculture, infrastructure such as roads, or for industry. Its mission statement reads:

“Wasteland is a degraded land which can be brought under vegetative cover, with reasonable effort, and which is currently under utilised and land which is deteriorating for lack of appropriate water and soil management or on account of natural causes.”

The NWDB’s mission is unambiguous, and its outcome is to see land merely in terms of what can be extracted from it. Thus, rock formations become quarries to feed our escalating construction industry; mineral-rich areas are mined or blasted; where there is nothing to quarry, mine or blast, the land is modified for agricultural or industrial purpose to make them “more productive”.

The Indian Space Research Organisation produced, at the expense of considerable resources, a Wasteland Atlas of the country that classified such land in various categories: Waterlogged Areas and Marshes; Mountains Under Permanent Snow; Savanna grasslands and pasture lands; Deserts, sand dunes, rocky outcrops and plateaus.

These four categories, cumulatively accounting for 20 per cent of our land mass, is deemed “waste” — a classification that ignores important natural realities. For instance, the Waterlogged Areas/Marshes are a critical habitat for waterbirds, and also essential for groundwater recharge and water security; the Mountains Under Permanent Snow comprise the trans-Himalayan region, the source of our greatest rivers; the Savanna grasslands host millions of livestock and pastoralists who depend on it for livelihood; and the deserts, dunes, rocky outcrops and plateaus are home to unique, irreplaceable fauna and flora.

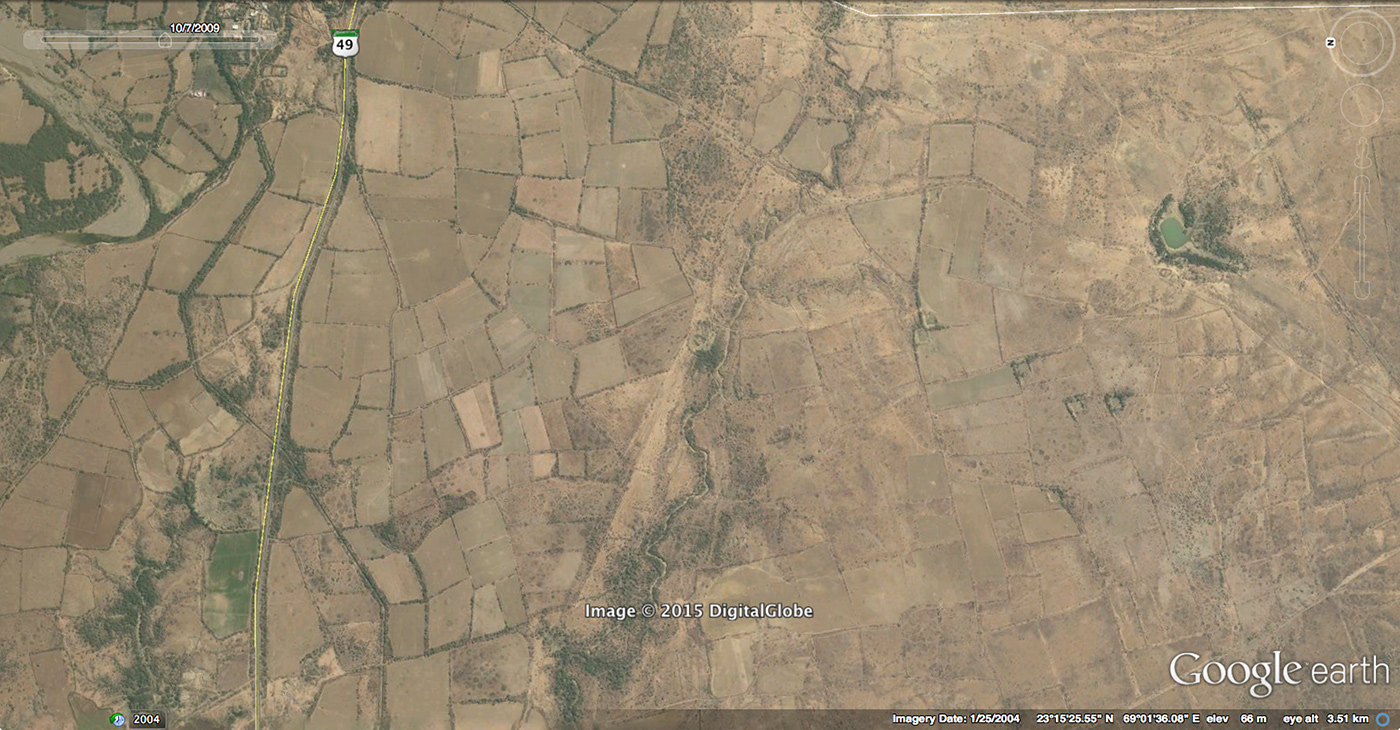

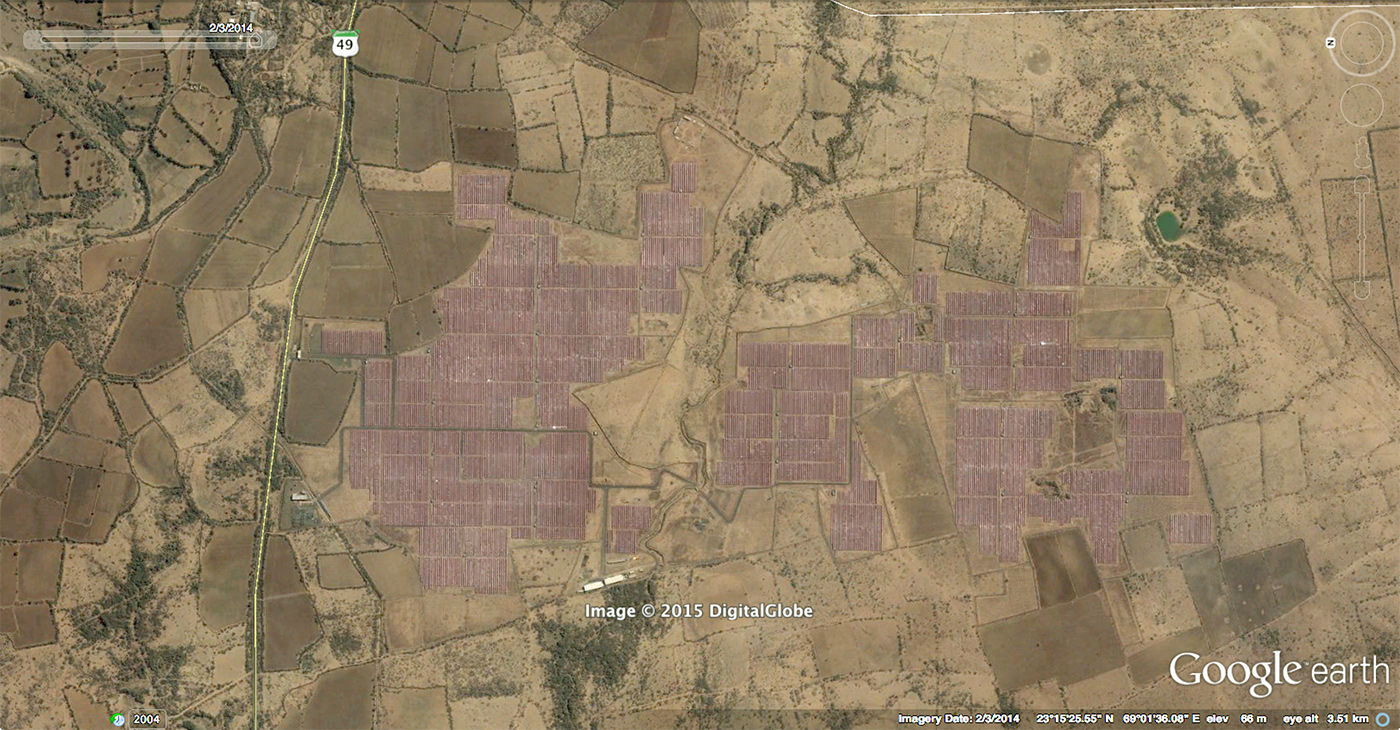

Below: The Nelia grasslands in Gujarat are one of the last home to the Great Indian Bustard. Less then 200 of this species are left and the land in these grasslands, after being tagged as ‘wastelands’, were given off to Adani Power Company to build solar farms.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/KalyanVarma__D120521-1000x500.jpg,(large)])

A host of government agencies work in tandem to convert these apparently marginal landscapes into “productive” areas. And sometimes, the same minister or department has reversed course — the most obvious example being Jairam Ramesh.

During his stint as As Minister for Environment and Forests, Ramesh proposed cordoning off large stretches of grassland to reintroduce cheetahs in India.

“It is important,” he told The Guardian in July 2010, “to bring the cheetah back as it will help restore the grasslands of India.”

When his portfolio changed and he became Minister for Rural Development, he did a policy about-turn and mooted the acquisition of savanna grasslands and other habitats for development. “States like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jammu & Kashmir, Andhra, Himachal have significant percentage of wasteland that can be exploited for development purposes” he is quoted in the Deccan Herald as saying in October 2013.

“States that have significant percentage of wasteland that can be exploited for development purposes”

Jairam Ramesh’s singling out the savanna is significant, because it is this type of grassland that has suffered the worst. Back in the days of the Raj, the British built extensive networks of canals and converted such land, till then the haven of the pastoralist, to agricultural use. Ironically, these canals changed the soil structure and landscape forever — and the once productive grasslands became wastelands in the real sense.

The Indian forest administration, responsible for managing and looking after the forests of India has continued this policy of ‘taming’ the wastelands. One of the primary objectives of the forest department is to plant and manage large plantations (usually exotic species) and use the timber from the plantations for various purposes. This is their primary revenue source and with this agenda, any open area is an opportunity to earn revenue.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/D102719-1000x666.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/D102719-1600x1065.jpg,(large)])

One of the recent initiatives by the government of India is the Green India Mission. The aim is to fight climate change by increasing the forest cover of India by 5 million hectares. And then there is Compensatory Afforestation Programme and Management Authority (CAMPA). For any land that is given out for mining in India, an equivalent amount of land area has to be afforested.

Both these initiatives believe that the only true eco-system is the one with tree cover and the Wasteland Atlas of India is their blueprint to go out and plant trees.

The idea that grasslands are unproductive is not sustainable. The economies, livelihoods and ecology of several countries — India is one of them — depend heavily on grasslands. The “wasteland” is an ill-defined political construct, and its continued prevalence is proving to be destructive of a vital link in the ecological chain.

There is a felt need for a policy shift from the colonial categorisation of landscapes to one that values land intrinsically, and does not see it purely from a “taxable revenue generator” prism.

It all goes back to a name. The rich diversity of the Indian landscape deserves better than the pejorative tag of “wasteland”.

***

For Dhangars, the nomadic shepherds, grasslands are backbone of life. Read about their way of life and how they migrate across these landscapes.

(The work of Dr Abi Ramim, Judith Whitehead and Subrata Singh provides much of the source material for this piece)

Kalyan, What a beautifully composed blog! Best wishes.

Correction: Dr. Abi Tamim Vanak

Has someone actually compared NRSC’s wasteland map with ground data to show the extent of ‘mis-classification’ as ‘wasteland’?

Very informative and action provoking! will wait for more! Keep it up.

Great !!!

Thank you very much for such awakening facts and knowledge.