Read part 1 of this series : The story of Suprita

We sat down to a feast — masala dosa, payasam and kadaboo, a steamed sweet-and-savory dish that is a special favorite of Lord Ganesha.

Prema – no one calls him by his real name Indu Shekhar, to his disgust – gently twitted my local contact Nisar, a Muslim, on his preference for meat-rich biriyanis. Prema and his family are Lingayats, conscious of their caste, proud of their vegetarian traditions.

The mid-monsoon rain of the morning had eased and humidity was building up. Indoors, the atmosphere was festive. Theertha, oblivious to protests, piled more food on our plates; Prema exchanged jocular barbs with Nisar and occasionally interrupted himself to brief me on local happenings.

Through it all I was conscious of a shadow, a sense that beneath the gaiety of Ganesh Chathurthi was a sadness kept in careful check. My eye strayed to the glass-fronted ‘showcase’ built into the opposite wall, crammed with idols of Shiva, Vishnu, Saraswati, Hanuman…

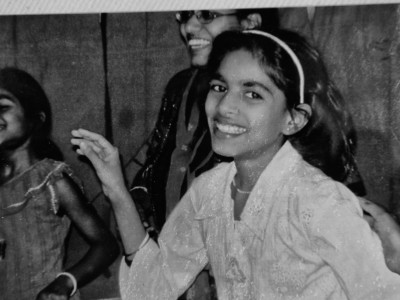

Two themes dominated this religious potpourri: Ganesha, represented in various sizes, shapes, materials and colors, and framed photographs of a young girl frozen in immortality.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124107-1000x667.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124107-1600x1067.jpg,(large)])

It was August 29, 2014. Four years after an enraged elephant had hurled Suprita to her death, we were feasting in honour of the elephant god.

Prema noticed my wandering gaze. “We have to celebrate this,” he said, suddenly serious. “It is a festival, after all. Ganesha is an elephant, sure, but how can we connect that to Suprita’s passing?”

A quiet descended in the room, the festive mood turned off as with a switch. “If one man kills another, can we kill all the people?” Prema asked. He seemed withdrawn, lost in the labyrinths of his mind. “If a bus runs over someone, can we burn all buses? My daughter was killed, but three of us are alive. So we celebrate Ganesh Chathurthi, we pray for those of us who are living, we seek his blessings for all of us.”

I had visited the Hassan/Alur area several times in the intervening months, to meet with the locals and to document the havoc caused by the elephants. And I had encountered this attitude repeatedly – a combination of loss and acceptance, tolerance and frustration, that I found hard to understand.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124066-copy-1000x666.jpg,(large)])

“Somehow,” Prema’s soft voice interrupted my thoughts, “that moment… that time was bad for us. What we have lost is gone, but we are alive, and we have to safeguard what we are left with.”

He wandered over to the shelf. With gentle fingers, he lifted out a wooden Ganesha he had hand-carved and ran his fingertips over it. It was as if he were reliving some loss; as if memory had turned tactile.

Of all the icons scattered around the house, this had been his daughter’s special favorite. It was before this small idol that Suprita had lingered for a moment of prayer before leaving home for the very last time.

“We pray to this one every year,” Prema said.

He placed the Ganesha carefully back in his place on the shelf, in the midst of images of the girl who had loved him.

***

Prema lives close to Kodalipet, a small town in Kodagu, at the southern edge of Alur taluka in the Hassan district of Karnataka.

Kodalipet is a junction town, connecting the coffee plantations of Kodagu in the south and the arid agricultural landscape to the north. ‘Town’ is a grandiose name for what is nothing more than a big bus-stand surrounded by the homes and shops of local traders.

From here, the landscape opens out into plantations, mostly of coffee and areca nut. Individual farms range from two to twenty acres, with the homes of the farmers nested within. Open, lush valleys with paddy intersperse this otherwise wooded estates.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/maps-1000x514.jpg,(large)])

A few kilometers south of Kodalipet, the Hemavati river flows in from the west and drains to the east towards Tumkur, one of the driest districts in Karnataka. In the late 1970s, the Gorur dam was built on the Hemavati, and it changed the DNA of the landscape forever.

The dam submerged 28 villages. The people thus displaced were allotted land that had previously been set aside as “reserved forest”, intended as the watershed for the reservoir.

The displaced villagers resettled in an area that was originally a dry habitat, but with the coming of the dam and consequent access to water, land use and crop patterns changed dramatically. What used to be a dry belt dominated by cotton and maize morphed into paddy fields and sugarcane plantations, with the wetter western side given over to coffee estates.

The locals have no significant memory of elephant sightings in the area before the dam came up. The Hassan district gazetteer of the 1970s lists deaths caused by the likes of snakes and leopards and documents compensations paid to next of kin, but these records do not mention elephants.

The first elephant sightings began in the 1980s. Over time, elephant herds of up to a dozen or more began to show up. At first they confined themselves to the surviving patches of forest, but as these began to degrade, they wandered into the estates and farmlands.

***

In those early days, elephants were objects of fascination. If an elephant showed up on a farm, it was a sign of divine blessing; if an entire herd passed through a farmer’s land, it augured a good yield.

During monsoons the locals, particularly children, competed to collect the water that had pooled in the deep footprints of passing elephants. This slushy cocktail of rainwater and mud, stored in plastic bottles, became the local ‘gangajal’, an essential accessory for poojas and a sovereign specific to be consumed when ill.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124230-1000x666.jpg,(large)])

They collected elephant dung, dried it in patties and used it as medicine for sick cattle. Prema recalls how, when Suprita was a child, he had burnt dried dung in the belief that the smoke would cure his daughter of an illness.

Over time the elephant herds grew in numbers, and the romance began to ebb. The herds whiled away the daylight hours in the shade of the few remaining patches of forest and, when night fell and the farmers slept, descended on the farms to gorge on the crops.

A herd of hungry elephants can make short work of the fruits of a season of backbreaking labour. Faced with such constant depredations, tolerance and affection slowly turned to anger and frustration. Prema recalls how, as a boy, he was deputed to stand guard over his father’s eight acres of paddy and to wake the elders at the first sign of the elephants. Prema and his friend Basavaraju made a treetop shelter, a machan, in which they spent their nights after a hard day working the fields.

The wheel had turned; a once benign presence had become a clear and present danger.

***

In 1984, the government took official note of the proliferation of elephants in the area and ordered that they be captured. Seasoned veterinarian Chittiappa was deputed to lead the operation.

Using captive elephants as shields, they closed in on the wild ones and knocked them out with tranquilizer darts. The stunned tuskers were roped, loaded onto trucks, and relocated to Bandipur National Park, a little over 300 km away. In order to keep track, the forest department team painted, in bold, large white lettering, a numeral on the sides of each elephant before releasing it into the Bandipur forest.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4125836-1000x666.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4125836-1600x1065.jpg,(large)])

In this fashion, Chittiappa and team released the third of the captured elephants in Bandipur and returned to Kodalipet. They drove from village to village, asking locals of any elephant sightings in the area. Yes, a villager told them at one such stop, “We saw a big tusker pass by a few minutes ago – it had a big ‘1’ painted on its side”.

Chittiappa’s laugh, as he recounted this story, had a rueful note. After all their time and trouble, their first captive had walked all the way back to the place it thought of as home.

In the narrative of man-animal conflict, interest groups often argue that habitat loss is one of the principal reasons for the face-off. Man, runs the argument, encroaches on the natural habitat of these animals and are thus to blame for the resulting chaos.

As with all vested arguments, this is only partially true. In the case of Hassan, the elephants are the encroachers, and the phenomenon Chitiappa observed, of a captured elephant trudging 300 km to return to the region, owes to what scientists call the McDonald’s effect.

At the height of summer, elephants find nothing to eat in the forests but dry grass and leaves. Inevitably, they are attracted by the lush sugarcane in the farms adjoining the forests. Over time, this becomes a habit, and the elephants begin to consider farms as eat-all-you-want buffets.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma_DJI00143-1000x750.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma_DJI00143-1600x1200.jpg,(large)])

This phenomenon explains the difficulty the forest department team had in ridding the region of elephants. Eventually, Chittiappa said, the team managed to capture 13 elephants and release them in Bandipur.

The relief proved to be temporary. Within four years, elephants began to make their presence felt again, to the distress of the farmers and irreparable damage to the crops.

***

It is next to impossible to accurately measure the cost of conflict.

In its report of 2007 the forest department, tasked with compensating farmers in the event of crop damage, identified a total of 38 villages affected by elephant depredation; in its latest report the number has swelled to 85 villages.

According to these records, there were 276 instances of elephants attacking humans during the period 1986-2006, resulting in 33 people killed and 243 others injured. Between 2008 and 2014, elephants killed a further 13 people in the area – an average of three human lives lost each year.

While these numbers provide some perspective, they are nowhere near enough to quantify the cumulative impact of wild elephants in an agricultural environment. During my many visits to Hassan and Alur, locals spoke of the problem in terms that went beyond the arithmetic of loss.

They talked instead of changes to the quality of their lives. After dusk, they said, no one ventured out of home except in dire emergencies, thus affecting their work and effectively ending all social intercourse. Approximately one in five children had stopped attending school, since it was deemed dangerous to walk down the roads in the early hours of the morning.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4122396-1000x667.jpg,(large)])

Everywhere you turn, everyone you speak to, has a story. Sharada, native of Timmalapura village, owns three acres of land. At no time in the past ten years had the farm been profitable – each season, they suffered crop losses due to elephant raids. Thus, each year saw the family plummet deeper into debt; each successive failure to harvest a full yield escalated these debts.

Finally her husband, helpless in the vicious cycle of depredation and debt, chose death as the only way out. He committed suicide. Sharada was forced to sell her land to pay off accumulated debt. Today, landless, she ekes out an existence as a daily wage labourer on any farm that will hire her, and dreams of when she was a farmer’s wife, with a position in society.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4122578-1000x667.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4122578-1600x1067.jpg,(large)])

In Hanumamahalli village, five women farm a small piece of land. All are widowed; all lost their husbands to elephants and to the resulting losses.

Such stories are the norm, not the exception. And underlying these stories, there is rage. But curiously, the collective anger is not directed at the elephants that are the proximate cause of their distress, but at what we collectively know as the “system” – forest department officials, NGOs, and assorted busybodies who, they believe, are too focused on the elephants and too blind to the plight of the people.

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4122535-1000x666.jpg,(large)])

Journalists are not exempt from the collective outrage. On one of my first visits to the region, in the wake of a conflict incident, I was mobbed, abused, pushed around and almost beaten up. You journalists, the mob said then, come to do your elephant stories and get your headlines and go away – no one cares what becomes of us.

***

Again, stories abound that can explain the anger the locals direct at the system. Prema is a case study.

One and a half months after losing his only daughter, two forest officials visited him at home to inquire into the tragedy.

Have you erected a solar fence around your property, they asked. Prema had, and said so.

How about your neighbors, the officials asked. This line of questioning made Prema suspicious – after all, what his neighbors had or had not done did not in any way account for his daughter’s death. The officials explained that the forest department would subsidize those who had installed solar fences at their own expense, and also offer help to those who want to install them. So Prema provided the details they sought.

Within a week, everyone in the area got an official notice stating that they will be held responsible for any elephant electrocuted by their fences.

“I wanted to electrocute those guys,” Prema told me, his fury still strong after all this time. “The next time an elephant attacks one of us, we will catch these guys and beat them up, ask them if they will take the responsibility.”

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4120262-1000x666.jpg,(large)])

It is this manifest lack of empathy that has the locals steamed up. Each time an elephant dies, they say, a battalion of journalists rushes to the spot to do sob stories; forest department officials ‘investigate’; Bangalore-based NGOs send representatives on ‘fact-finding’ missions. “But,” says Rangegowda, “when my son died, no one came. No one.”

Over the years, Rangegowda has piled up enormous debt owing to crop destruction by elephant herds. Forest officials once beat him up when he went into “their” forest to collect wood. Finally, when one of “their” elephants killed his son, he went over the edge.

I was present at a village council meeting organized by forest department officials, at which NGOs representing the interests of elephants were present. There, I witnessed the full extent of Rangegowda’s fury.

“We are farmers,” he screamed at the officials and NGOs. “It is us that feed the elephants, not you animal lovers! If you love elephants so much, live here in their midst and face what we face – don’t live far away and teach us how to live our lives…”

],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124165-1000x666.jpg,(medium)],[https://www.peepli.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/KalyanVarma__4124165-1600x1066.jpg,(large)])

His rage boiled over as officials sought to calm him. “Give us back our gun licenses,” he yelled. “Give us one year of immunity. We will solve our own problems.”

As he raged on, I realized that his anger, stemming from official shortsightedness, had crystallized into a hard-hearted desire for drastic action. On the sidelines of that meeting, I attempted to reason with him.

He grabbed my shirt collar in one hand; the other, clenched in a fist, he waved in my face. “Since the last time you people came here and promised to resolve the issue, my son has died,” he screamed, his face close to mine. “Will you accept that you are responsible for his death? Will you accept that the blood of my son is on your hands?”

The Hassan-Alur region is by no means ground zero in the struggle between man and elephant – in fact, such conflicts are far greater, far more serious, in other terrains. But the events of that day convinced me that here, a flashpoint had been reached; the collective stance had hardened. Either the elephants had to be removed and the cycle of death and destruction ended, or people would take matters into their own hand, gun license or no.

“We cannot just leave this land and go elsewhere,” Prema, one of the more moderate voices to be heard that day, explained to me later. “This is our land, this is our livelihood. We have nowhere else to go, and we know of no other means to live. We are not well educated – we can’t just migrate to cities and look for jobs there.

“We work hard, and we earn just enough to survive. All we are asking for is to be allowed to do that.”

Note: This is part two of my ongoing narrative on the conflict in Hassan. Part I is The Story Of Suprita and part III is The Elephants Must Go where an activist court and a dedicated task force come together to find a solution.

Thanks to Divya Mudappa, M D Madhusudhan and Dilan Mandanna for their extensive research and analysis that informed this story, and to Nisar, my local guide at Kodalipet.

Very interesting turn of nature. Is anyone doing something about the elephant numbers?

Is there a way found to re – direct their path back to the forest?

Kalyan,

Another great article explaining the current ground situation. Eagerly waiting for the 3rd part.

Thank you.

Feeling sorry about Suprita and other families, nor the people or the elephants can be blamed. Such human animal conflicts can be resolved for a while but not for a long. Loss is a loss for both the species.

I find this very interesting article. Sad for Suprita and many more.No parent should endure this.Deforestation caused this , I agree both with elephant and farmers.

Hi Kalyan,

Once again a really thought-triggering sequel in this trilogy. I am left with mixed feelings – of rage, helplessness, frustration. I cannot claim to understand what the locals are going through. And I can’t bring myself to blame the elephants either. Is there really a solution? Not as long as we are shortsighted and see what we want to. Thank you for very evocative writing.

None to blame !! Nature has its own ways to balance .. what about the loss of life, can that be balanced ? .. its obvious that people make livelihood there.. What can be the solution? Every action has its own pros and cons … Can forest officials make farming around the forest for the elephants to graze peacefully.. just a thought .. not sure how feasible !!??

This is such an amazing balanced viewpoint and series. thank you so much for bringing the human face to life. This must be so frustrating for the farmers when people seem so much more enraged and seem to care more about the elephants than them.